Hidden History on the Blue Mountains Trail

- Jared Kennedy

- Sep 28, 2021

- 6 min read

It's no surprise that a 530-mile route through Northeast Oregon would include some amazing landmarks along the way. The Blue Mountains Trail is almost entirely on existing trails and old gravel or 4x4 roads, and it traverses a long legacy of human use, extending from the Native Americans whose livelihoods and cultural traditions have been sustained from these lands since time immemorial. Western settlement altered these lands in a myriad of ways that we will see for future generations. And yet, the public lands of Northeast Oregon sustain some of the oldest living organisms found in North America.

We prioritized routing the Blue Mountains Trail in such a way that hiking the full route provides a deeper connection to the region. Here you can experience the region's flora and fauna, and also the living human history that leaves deep artifacts—both physical and emotional scars—that we regularly encounter in our work to protect, connect, and restore the wild lands and waters where both native species and human communities thrive.

What follows are some of the unique, largely hidden landmarks and natural features that are found hiking along the Blue Mountains Trail. The list is most certainly incomplete; we invite you to share more parts of the hidden history of these landscapes with us (use the comments below or send an email to ghcc@hellscanyon.org).

The world's largest organism

In Malheur National Forest, along a patchwork of U.S. Forest Service Roads between Clear Creek and North Reynolds Creek, the Blue Mountains Trail runs on ground holding a mycelium network of an immense Armillaria ostoyae mushroom, popularly referred to as a honey mushroom. This specific Armillaria is also called the Humongous Fungus and it holds the title of the world's largest organism. This is the largest underground network of Armillaria mycelium found in the area. It encompasses 2,385 acres and spans over 2 miles from end to end.

These mushrooms are tree killers. The mycelia of Armillaria ostoyae consumes the roots of living trees, and this particular honey mushroom continues to grow at a rate of 1-3 feet per year. Based on the area of the mushroom, it's estimated that this organism is between 1,900 and 8,650 years old! The mushrooms fruit in the fall, and can be seen sprouting from the trunk of an infected tree.

The Humongous Fungus is found approximately 8 miles south of Austin Junction on Section 7 of the Blue Mountains Trail. More information about this amazing organism is available from the U.S. Forest Service.

Oregons's oldest tree

Hidden along the slopes of Cusick Mountain in the Wallowas, an ancient Limber pine (Pinus flexilis) has stood for thousands of years. The exact age of the tree is undecipherable because the tree core rotted out long ago, but the living tree is estimated to be between 2,000 and 3,000 years old. It was first "discovered" by Baker City historian Gary Dielman, and was named the Dielman's Monarch in a 2009 Oregon Field Guide episode that featured the tree.

While the Oregon Field Guide episode with Gary Dielman is no longer available, twin brothers Darryl and Darvel Lloyd hiked to the ancient tree with an Oregonian film crew (you can watch the video below).

Section 1 of the Blue Mountains Trail runs along much of the eastern and southern base of Cusick Mountain as it crosses Hawkins Pass and continues on the South Fork Imnaha River. While it may be enticing to seek out Oregon's oldest tree, we highly encourage watching the video and taking pleasure in hiking in the tree's general vicinity (to protect the landmark and avoid some challenging and dangerous terrain).

A 140-mile hand-dug water ditch

In the late 1800s near the town of Unity, a canal known as the Eldorado Ditch was hand-dug over the course of 15 years by Chinese laborers to provide water for placer mining. The ditch was approximately 140-miles long, transporting water from the Burnt River to Malheur City. It still exists today but no longer carries water for much of its length. The ditch sparked animosity and malfeasance between the gold miners who commissioned the ditch and cattle ranchers opposed to transporting water away from agricultural use in the Burnt River Valley. The gold mining boom went bust before the cost of digging the ditch could be recuperated.

Mike Higgins, one of the founders of the Blue Mountains Trail, whose family originally emigrated to the Burnt River Valley in 1863, wrote a book about the Eldorado Ditch, along with Les Tipton, called Ditch Walkers and Water Wars. We highly recommend reading it for an in-depth history of the Eldorado Ditch. The Blue Mountains Trail passes over the ditch in Section 7 not far from the Humongous Fungus.

Ghost towns of the gold mining era

Gold mining had its heyday in Northeast Oregon in the 1800s, going through a boom, bust cycle similar to the more well documented gold rushes in California and elsewhere in the United States. As you'd expect, remnants and artifacts of the boom are still intact. From the Elkhorn Crest to John Day, and most prominently in the vicinity of Sumpter, the mining history of Northeast Oregon, with numerous working and abandoned mines and rock piles from placer mining, is on full display.

The Blue Mountains Trail runs passed an old mining cabin at Tub Springs in the heart of the North Fork John Day Wilderness. The trail's longest bushwhack and cross country ridge walk is needed to route around a working patented mining claim at Cable Cove, and a few miles further along the trail, it runs by Cabell City, a true Oregon ghost town.

Cabell City was never much of a city, but it was a gold mining camp with structures that remain today. You can find the last wooden grave marker in the small cemetery. Cabell City even shows up on Google Maps, certain to lead some wayward adventurer astray (the rough gravel road leading to Cabell City is not suitable for most vehicles). The ghost town is a short detour from the main trail route in Section 6 between Baldy Lake and Crane Creek Trailhead.

The recently rediscovered extinct Kay apple tree

When the Oregonian recently published an article about the newly rediscovered Kay apple tree in Flora, Oregon, Naomi "the Punisher" Hudetz, one of the Intrepid Trio who completed the first thru-hike of the Blue Mountains Trail, emailed me to let me know she'd eaten one of the apples from that very tree. While she didn't mark the exact location of the tree, she did say the apple was delicious.

The Kay apple tree was rediscovered through the efforts of the Temperate Orchard Conservancy, an organization that works to preserve and share the genetic diversity of tree fruits that are grown in the temperate climate zones of the world.

The Nimiipuu Trail - Nez Perce flight from Oregon

Dug Bar on the Snake River in the heart of Hells Canyon is best known as the place where the non-treaty bands of the Nez Perce (Nimiipuu) left their ancestral lands in Northeast Oregon for the last time. Upon crossing the Snake at Dug Bar, Chief Joseph, his brother Ollokot, and hundreds of Nez Perce warriors and their families, spent months traveling through Idaho and Montana, fighting many battles with the U.S. Cavalry, in an attempt to reach Canada and seek refuge. Just 50 miles from their goal, they were forced to surrender. The route taken by the fleeing Nez Perce is now a National Historic Trail administered by the U.S. Forest Service.

A few recent books, including Thunder in the Mountains by Daniel Sharfstein, chronicle the events that led up to the Nez Perce's flight from their homeland.

Today, we work closely with members of the Nez Perce Tribe and other partners in the Blues to Bitterroots Coalition and on the Camas to Condors program. Section 2 of the Blue Mountains Trail also follows parts of the Nimiipuu Trail from Dug Bar on the way to Buckhorn Overlook.

Site of the first large federal timber sale in the Blues

The federal government created the large national forests through the Organic Administration Act or 1897 and converted large areas of heavily logged private timber land to federal ownership with the Weeks Law of 1911. Initially the goal of the laws was to improve and restore forests that had been degraded by logging without laws, but at the time, the new federal foresters considered old growth a form of waste, of forests not being put to their maximum potential.

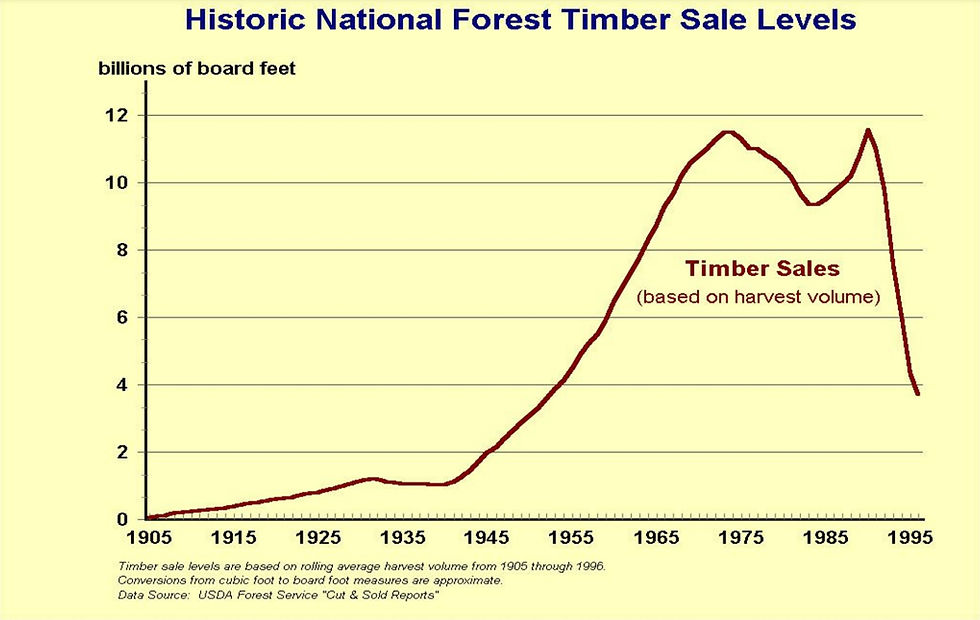

In 1916, the first large federal timber sale in the Blues was offered along the Middle Fork John Day River. In all, 14,600 acres of old growth ponderosa pine were sold in this first sale, and by 1928, loggers had cut 20 million board feet per year. While the logging of federal forests didn't pick up in earnest until World War II (see chart above), the Blues became the early testing ground for federal industrial logging.

The Blue Mountains Trail routes through the location of the 1916 timber sale as it descends from Vinegar Hill and runs along the Middle Fork John Day River on the Davis Creek Trail. Bates State Park is now located at the site of the old Bates Lumber Mill, where much of the trees were milled following the logging. You can read more about the history of logging and grazing in the Blue Mountains in Forest Dreams, Forest Nightmares by Nancy Langston.

Comments